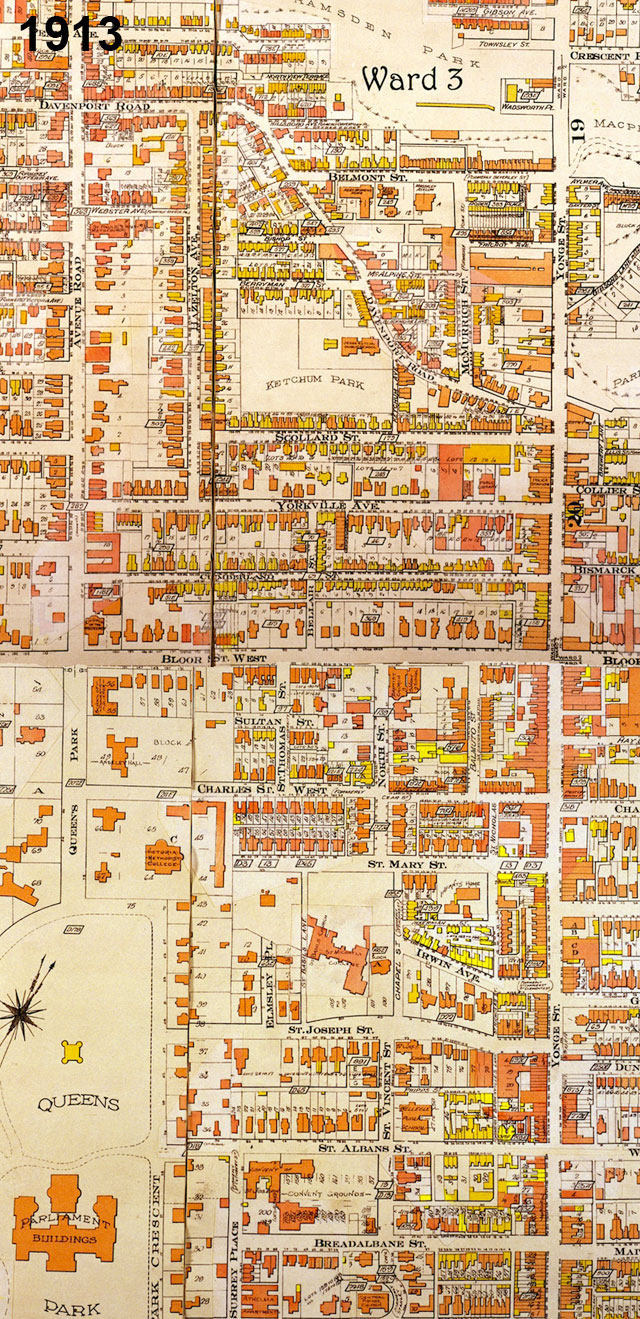

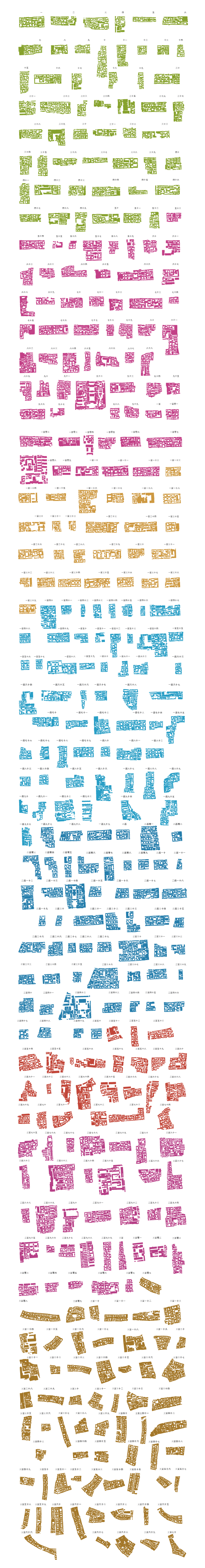

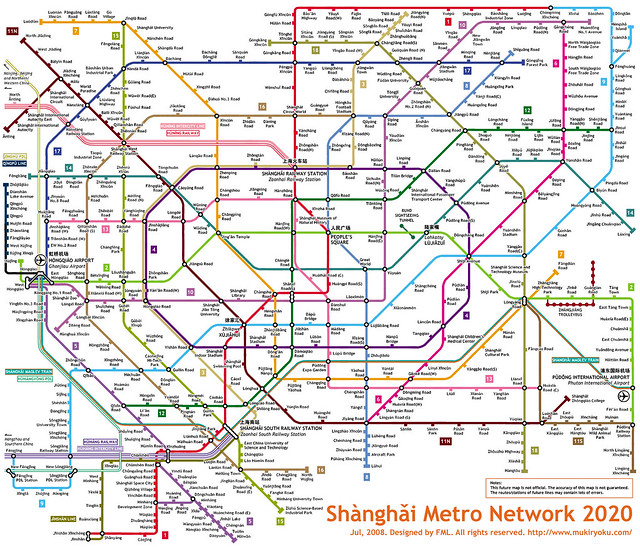

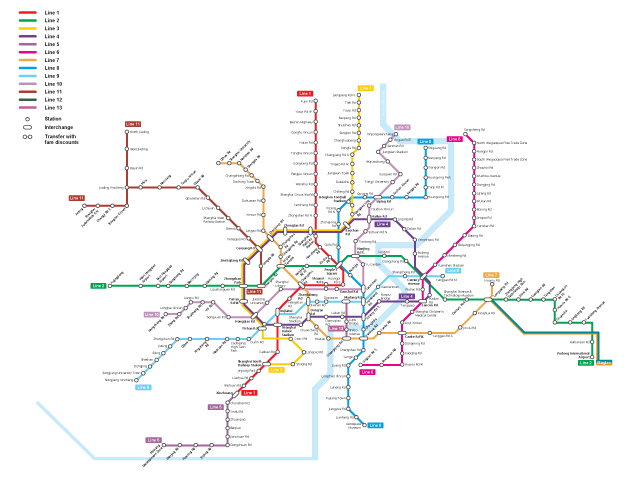

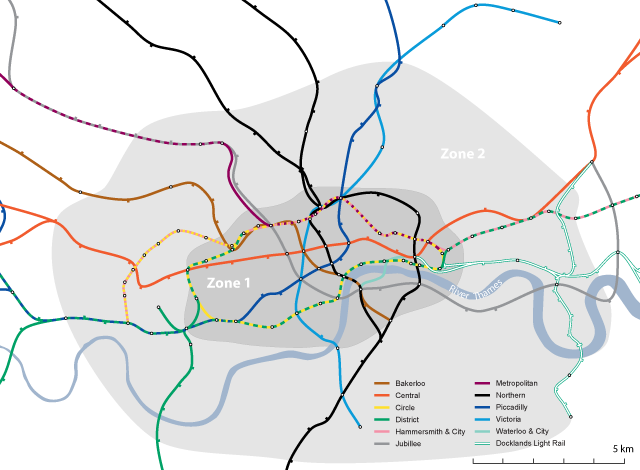

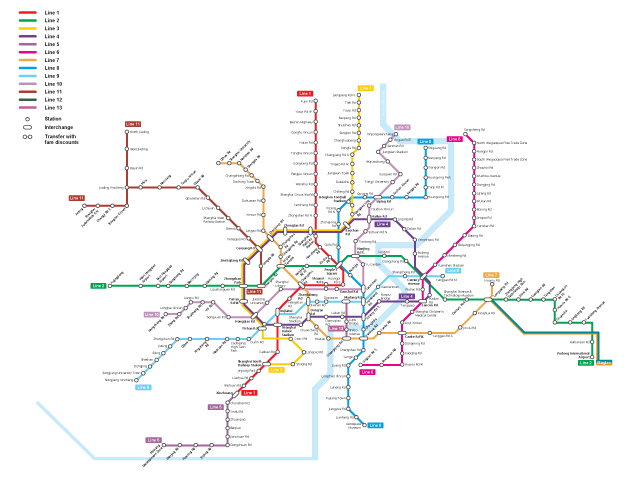

Shanghai Metro Network in 2020 in style of the famous London Tube diagram, by Flickr user Kzaral

Now that Shanghai’s Metro is officially the longest subway network in the world (by track length), I thought it would be interesting to do a comparison between it and the long-time title holder that it displaced, London’s Underground.

The first major difference is that Shanghai’s Metro is still expanding, very fast. By 2020 it intends to have added over 350km in new lines and extensions, almost doubling its network length, and in China, when the government intends to achieve something within a 10 year timeframe, they generally succeed or come close. With currently 420km of network, Shanghai’s Metro earlier this year passed the Underground (which has 402km, although I believe that doesn’t include the Overground line or the Docklands Light Railway) after opening 3 new lines and long extensions to 2 other lines (creating a subway link between the city’s two airports) in time for the opening of the Shanghai Expo. The shocking thing about the 2020 expansion plan is that it will make the above diagram (created by Kzaral aka FML in the style of the famous Tube map) a reality and not a fantasy. All this from a system that only opened its first subway line (appropriately called Line 1) in 1995. Yes, you read that right, 1995.

The second major difference is that there is no suburban commuter rail system in Shanghai that compares with those in cities like London, Paris and Tokyo, where the railway network is essentially operated as a secondary rapid transit system with longer station intervals than the subway, generally with an interchangeable fare system. In Shanghai there is only the regular railway network which is not run anything like a metro rapid transit system, but clearly prioritizes long-distance and high-speed trains, and largely services only 2 stations within the inner city, the main station and the south station. This is a severe deficiency in a city as large as Shanghai since it is those suburban commuter rail systems that ensure quick and efficient travel into the city centre from the suburbs, and in Shanghai make no mistake, those suburbs are often nearly as high density as the inner city. This is the reason that even with what seems on the surface like a fully implemented subway system, Shanghai actually desperately needs to push ahead with the rest of the subway system expansion program, because most of the new lines and track length will be servicing the vast suburban areas in an attempt to make up for this lack of a commuter rail network. Time will tell whether this model actually services the suburbs with better all-round transit than the commuter rail approach, and at least Shanghai has the density to justify subways in the suburbs. However, as of now, the subway model predetermines extremely long subway rides from the suburbs rather than quicker commuter trains that stop less frequently and dump you in the city centre to jump on the subway to your destination. In contrast to the London commuter rail paradox of someone living in a rural village outside the city potentially having a significantly shorter commute than someone living in the inner city itself, in Shanghai the emerging paradox (fueled by extensive high-speed rail expansion) is someone living in a city 300km away from Shanghai (eg Nanjing) having a shorter commute than someone living in Shanghai’s suburbs (the new Shanghai-Nanjing train can do the 300km trip in 73 minutes).

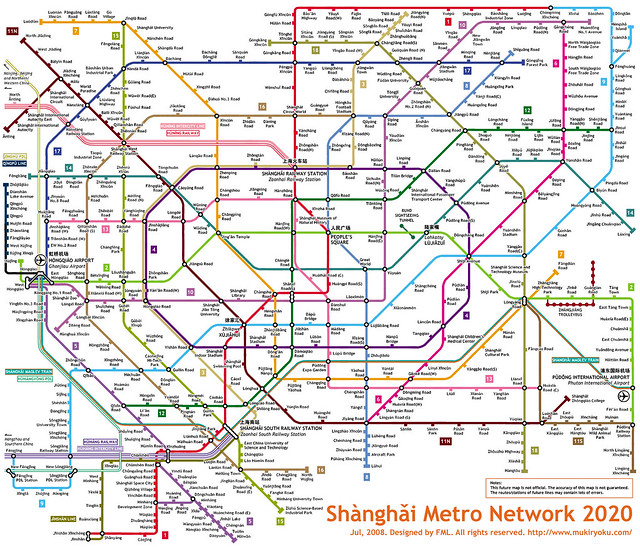

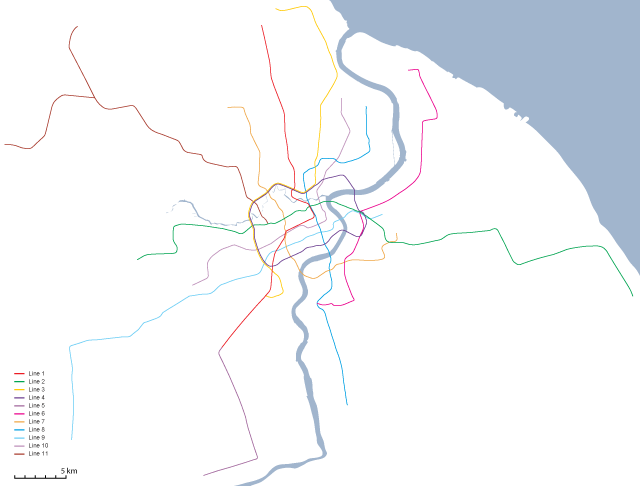

Full current regional network diagram of Shanghai Metro, July 2010, move over with mouse to show 2020 expansion (credit: Shanghai Daily)

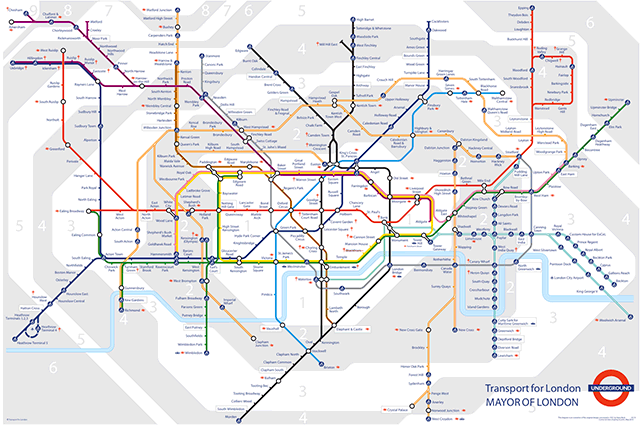

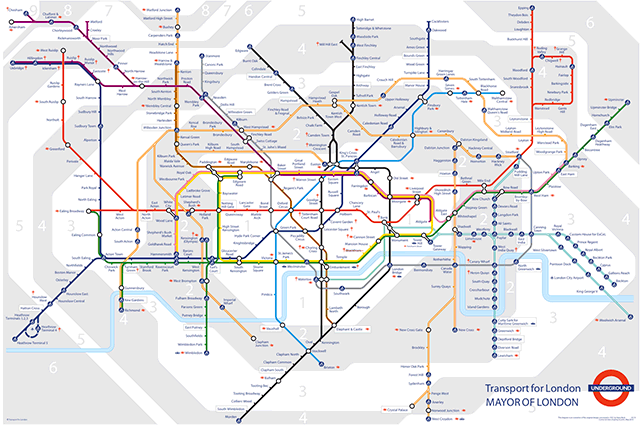

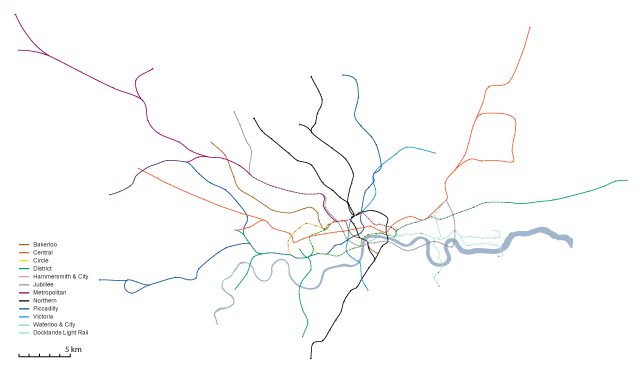

Full regional network diagram of London Underground (including Overground and Docklands Light railway) (credit: TfL)

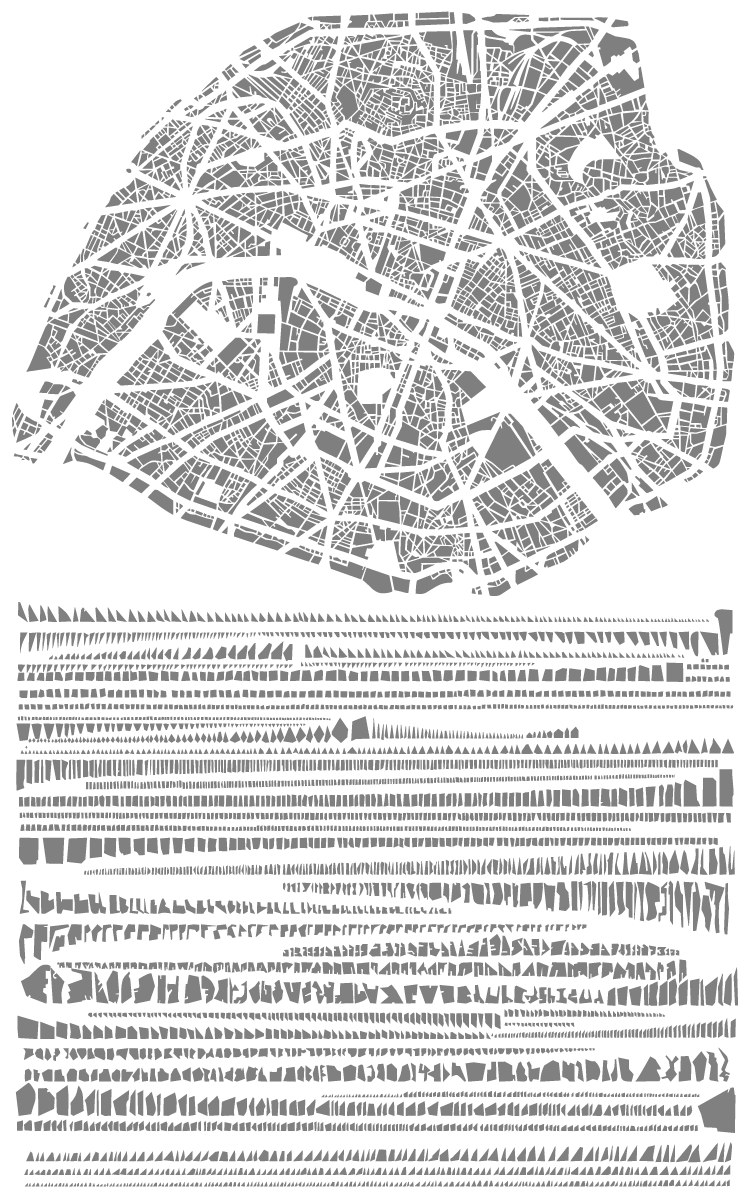

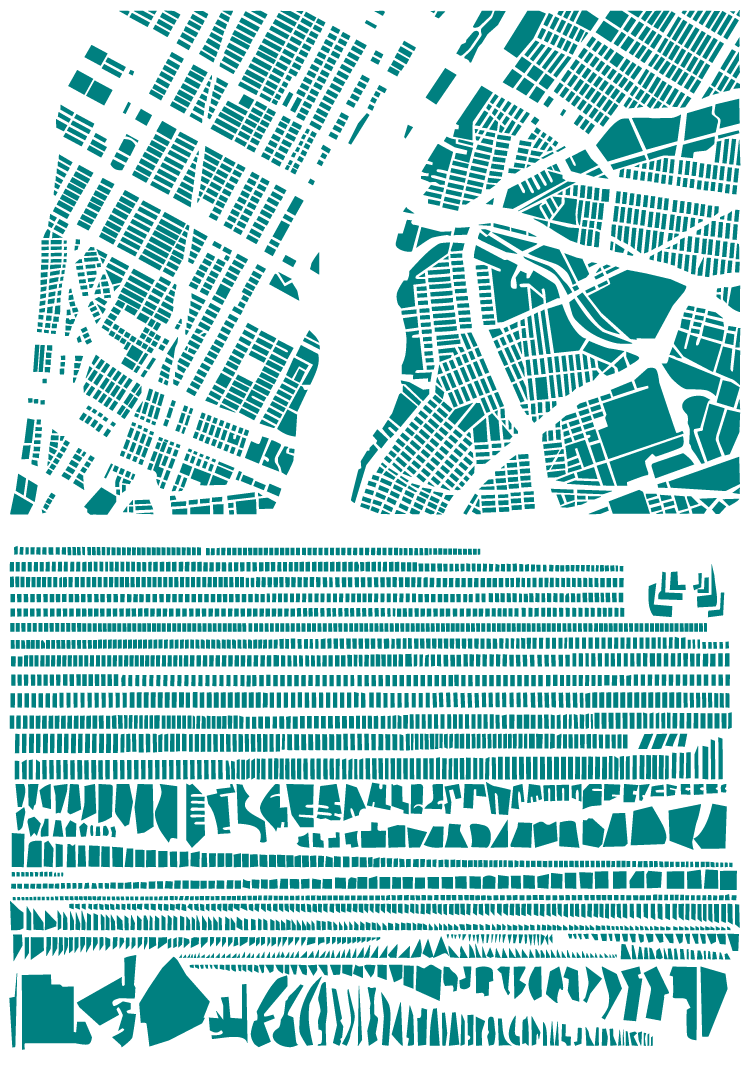

The Shanghai network map is quite a bit less diagrammatic than the iconic Tube map, but a comparison reveals the different biases of each system. In particular, the primary strength of the London Underground has always been in movement around inner London’s central areas for which the coverage is excellent. This bias is highly demonstrated in the famous Beck Tube map in the extremely large size of Zones 1 and 2 compared to the suburban zones, although this was no doubt to allow clear reading of the closely spaced stations and line layouts. In Shanghai’s case the emphasis is clearly on the radial pattern of suburban lines rather than the central area, and this will only increase with the future expansion plans. In particular, notice in the two maps that Shanghai’s circular Line 4 (the purple irregular circle) and London’s Circle Line (yellow) appear about the same size in the two diagrams, but Line 4 encloses an area 3.6 times bigger than the Circle Line (62.9km2 vs 17.5km2, by my measurements).

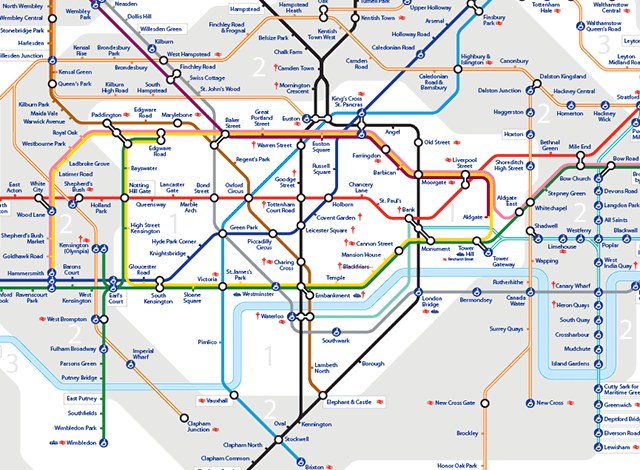

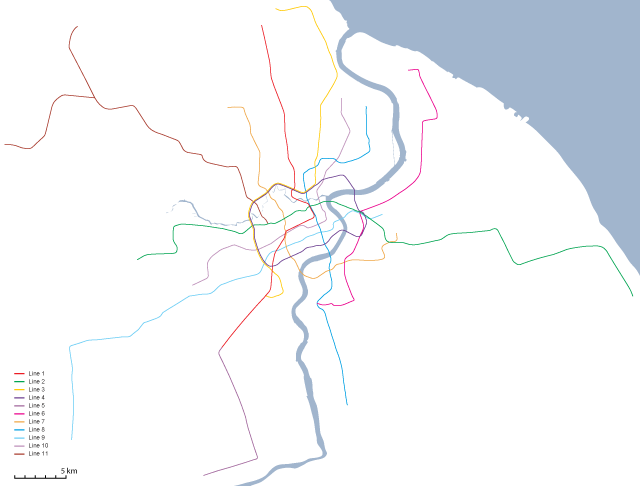

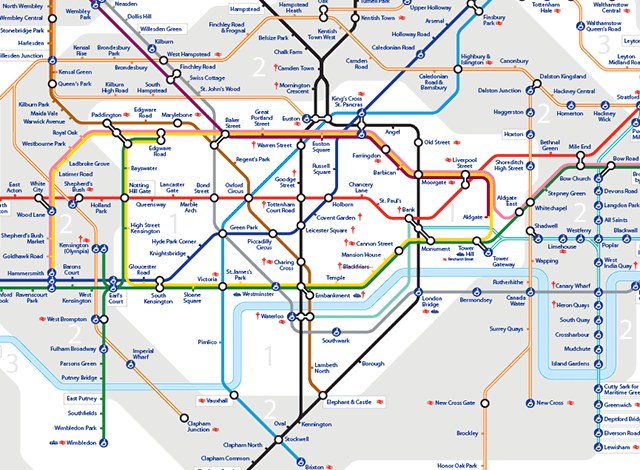

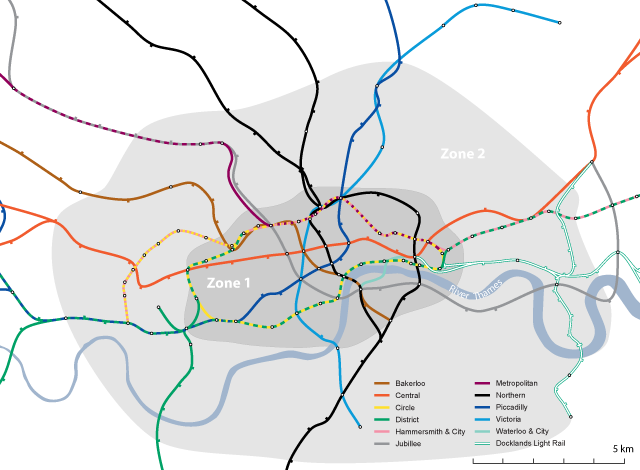

Central area diagram of Shanghai Metro, July 2010, move over with mouse to show 2020 expansion (credit: Shanghai Daily)

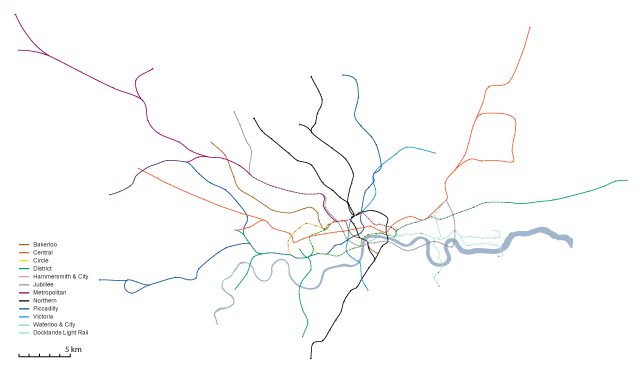

Central area diagram of London Underground (including Overground and Docklands Light railway) (credit: TfL)

Now perhaps Shanghai’s central area is larger than London’s thus justifying a larger scale for the circular line, or perhaps Line 4 shouldn’t be used to compare either its function or service area with the Circle Line. Unfortunately, this is where the diagram maps start to fail us, because it becomes hard to understand whether there’s a significant difference in service quality or convenience as a result of this difference in scale. For that we need a geographically accurate representation of both systems that we can look at and measure at the same scale. So here we are:

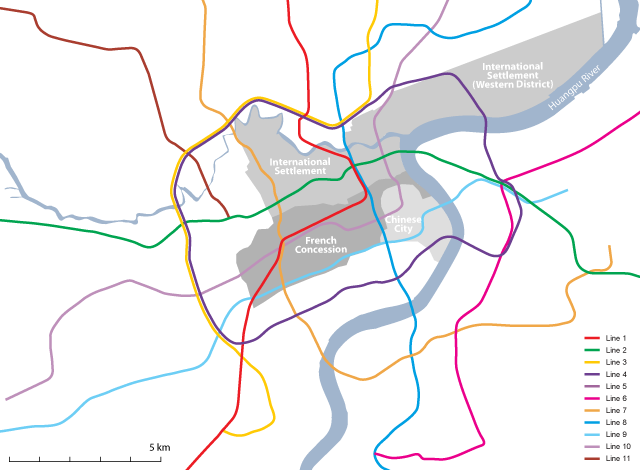

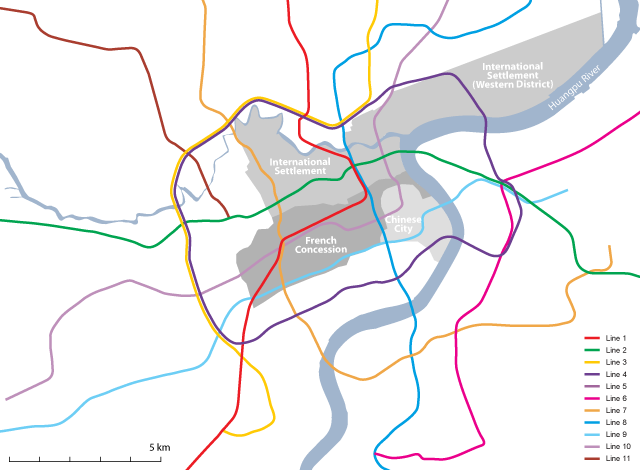

Central area of Shanghai Metro, July 2010 (geographically accurate, showing historic city centre districts)

Central area of London Underground (geographically accurate, not including Overground and railway network), move over with mouse to show major parks of central London

What is most noticeable right away is that London’s Circle Line falls entirely inside the Underground’s Zone 1 which can easily be taken to represent central London, although anyone who knows London will know that quite a few districts considered “central” fall inside Zone 2 instead. Additionally, the London Congestion Zone (which could also easily by used as a boundary for central London) largely mimics Zone 1 with a few variations but enclosing an area of the same size. This means that the Circle Line directly services numerous important destinations right within central London, while it’s tracks are shared with 3 other lines over different parts of the route meaning every station on the Circle Line allows transfers to a different line. There are additionally 18 railway stations and termini within the Underground’s Zone 1, 6 of them directly serviced by the Circle Line, allowing direct connections for commuter rail passengers.

For the Shanghai map I have included historic districts of the city which include the Old Chinese City and its port district along the Huangpu River, the French Concession and the International Concession. Note how Line 4 essentially entirely runs outside the central historic districts. In fact the large Western District area of the International Settlement was the least developed part of all the historic districts, and remains a rather distant feeling part of the city. Strangely, Line 4 also avoids directly servicing Shanghai’s new financial centre at Lujiazui in Pudong on the east bank of the Huangpu River, although it does service Shanghai’s main railway station, although this station itself falls outside of the historic core of the city. The route of Line 4 seems to have largely been decided by the convenience of using old railway right-of-ways and the construction of Shanghai’s Inner Ring Road rather than determining what would best service the city’s future transportation needs.

In general, central Shanghai today is often considered to be anything within the Inner Ring Road, but this definition does not relate to the historic city in any way (particularly on the Pudong/eastern side), while functionally it might relate to the modern reality. I calculated that the old districts of Shanghai I included on the map above cover about 38km2 which funnily enough is around the same size as London Underground’s Zone 1, but nevertheless Line 4 is far bigger than these historic districts, and also misses other new centres at the edge of the historic districts such as Xujiahui and Lujiazui. The real implication of this comes when you examine numbers of stations: London’s Circle Line has 27 stations over 21km around the circle (all of them with an available interchange to at least one line, and many of them directly servicing major destinations), while Shanghai’s Line 4 has 26 stations over 33.7km with interchanges at 16 stations and servicing relatively few major destinations. All together there are 64 Underground stations in London’s Zone 1, but only 34 within Shanghai’s Line 4 (not including Line 4 stations themselves, since I consider them to be outside the city centre), even though London’s Zone 1 (at 38km2) is almost half the size of the area inside Line 4 (62.9km2).

Full current regional network of Shanghai Metro, July 2010 (geographically accurate)

Full regional network of London Underground (geographically accurate, not including Overground and commuter railway network)

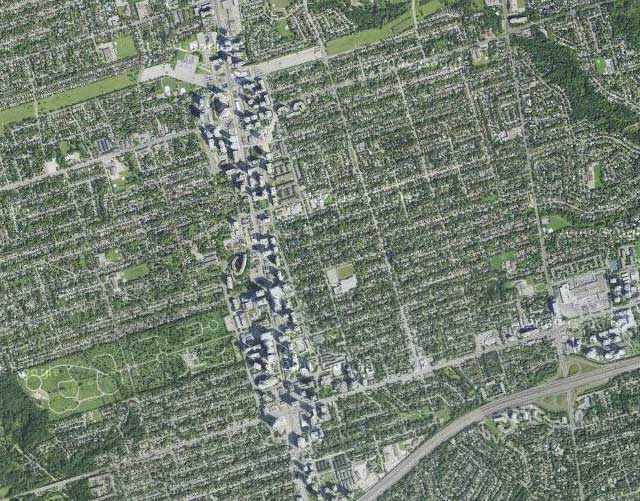

Now of course in terms of urbanism, Shanghai and London are very difficult cities to compare, so it may not be fair to dismiss the route of Shanghai’s Line 4 as inappropriate and inconvenient compared to London’s Circle Line. It’s certainly true that central Shanghai is not and will not be served as well by its Metro as central London is by the Underground, but in many ways this reflects the evolving functional reality of Shanghai and the decreasing importance of the historic districts in the future development of the city, largely resulting from the budding desire to protect the historic heritage in the inner districts. But given the densities of suburban Shanghai and the far lower car ownership rates and the lack of commuter rail options, Shanghai does desperately need to improve transportation in the suburbs, since in the future Shanghai’s suburbs cannot be allowed to rely on automobile transportation to the same degree as London or other western cities because at these densities, congestion will be unavoidable and nightmarish. If you look at the entire cities’ networks in a geographically accurate representation (see above), the systems are actually highly comparable, and the area covered also comparable, with the caveat that without showing London’s commuter railway network, London’s Underground appears to have less coverage than Shanghai’s current system (particularly south of the Thames which has always been poorly serviced by the Underground itself but is quite well served by railway). Perhaps the most shocking thing is that London has been benefiting from Underground services since 1863, which given the massive population and size of Shanghai, makes you wonder how on earth Shanghai functioned at all before the first subway line opened in 1995!

Lastly, there are a few things Shanghai could do to help improve the Metro beyond the constant expansions. It’s very odd that none of the lines (even the most popular, Lines 1 and 2) operate much beyond 11pm, and in fact many of the lines cannot be relied upon after 9pm or 10pm (although for some of them, running has been extended during the Expo). Additionally the station dwell times seem excessively long compared to most systems I’ve used in the world – the slow speed of the train arrival, the delay until the doors are opened, the delay before the train leaves after the doors have closed, all add time at every station, which compounds itself on longer rides. I don’t know if the introduction of automatic train operation will be able to speed up these times or whether they relate to safety concerns with the sliding glass platform barrier doors at most stations. Lastly, crowding on trains even during off-peak times and late in the evening seems to indicate that Shanghai’s Metro should increase operating frequency on many of its lines, and suggests that there is clearly high demand for later, more frequent subway operation.

Credits: The Underground geographically accurate maps are based on the work of London Underground geographic maps group at Wikimedia Commons – station locations are accurate, but line routes between stations have been interpolated.