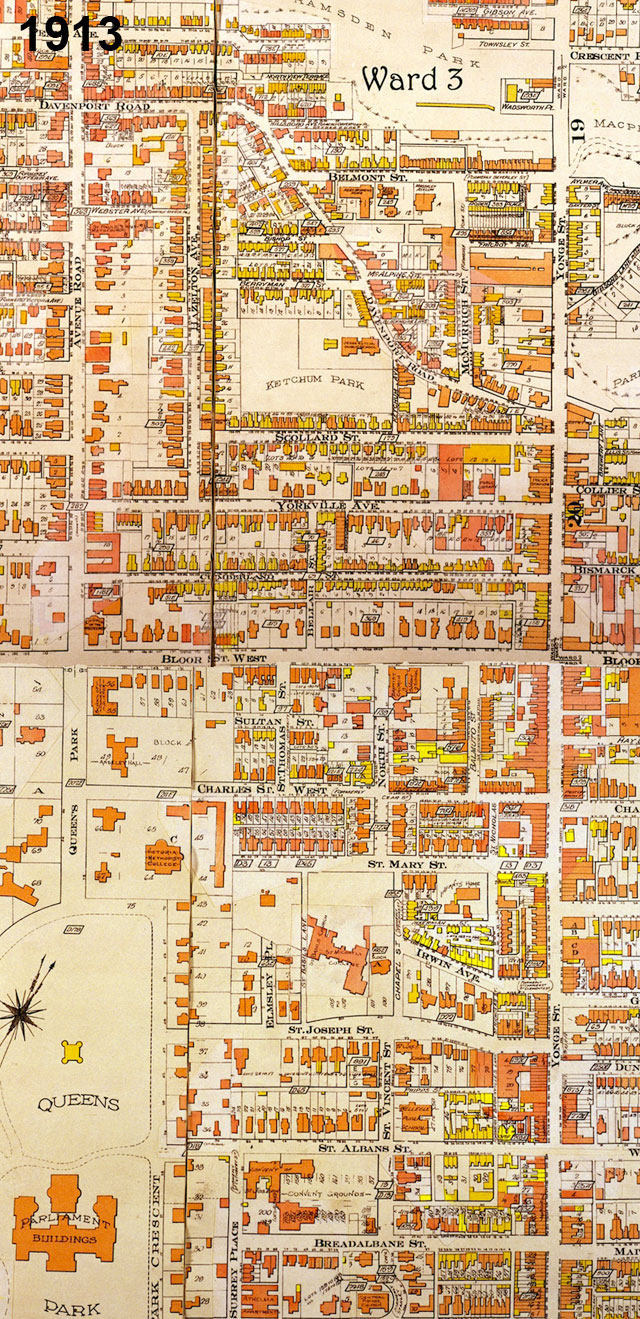

Before Bay St Divided Yorkville

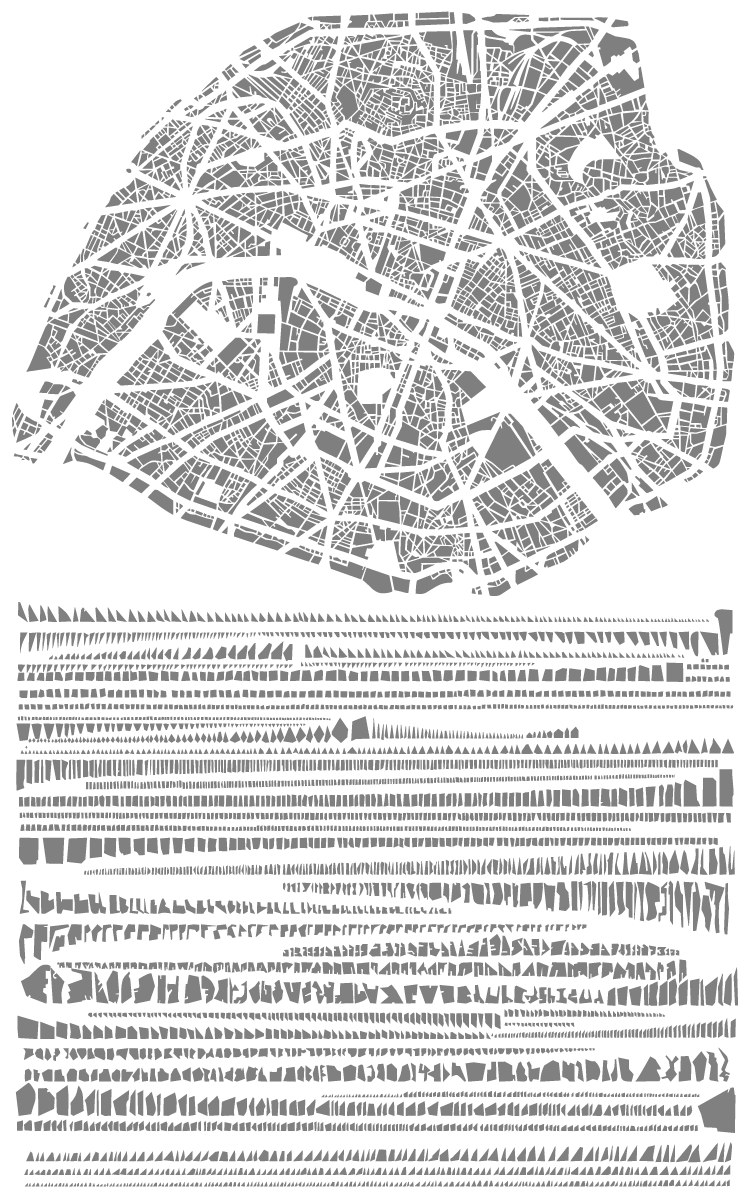

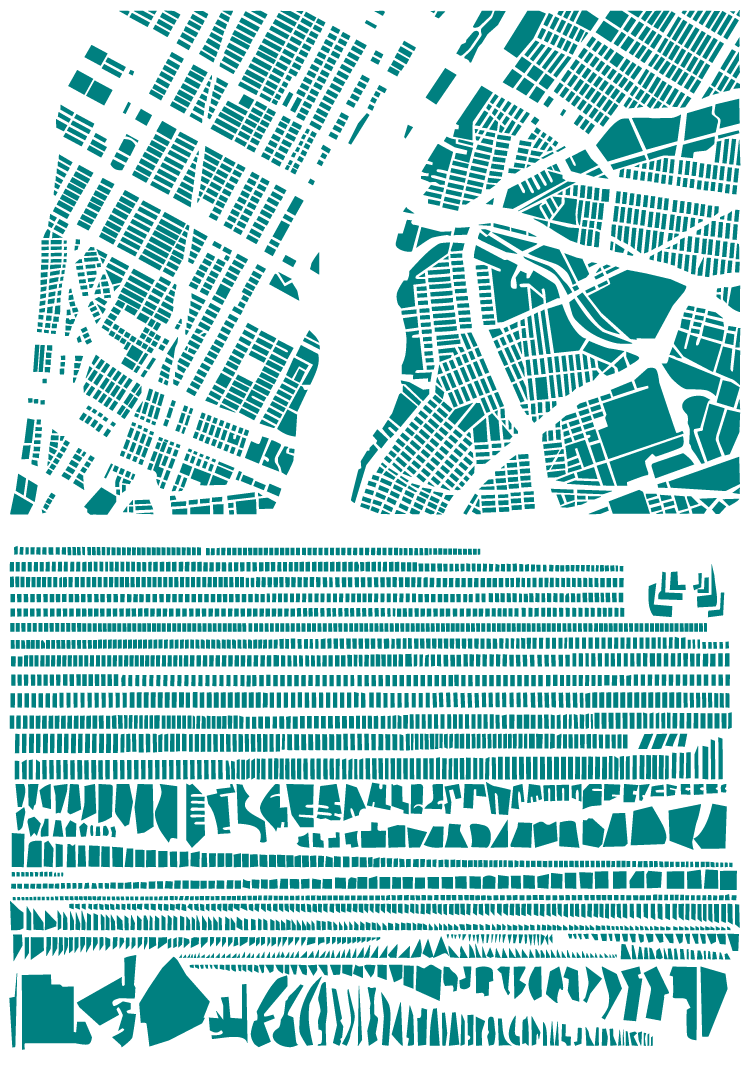

Goad Atlas fire insurance map showing the area between Yonge St and Queen's Park/Avenue Rd from near College St to Davenport Rd in 1913 - move over with mouse to see the same area in 1924 after Bay St was cut through

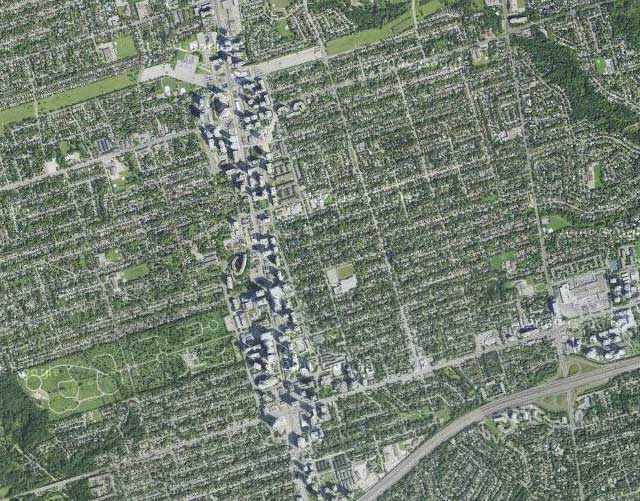

One of Toronto’s little historical secrets is the mystery of why Bay St does such a large jog at Queen St. History buffs may know the answer, but I only recently came upon it myself, and it answered many questions I’d long had about the strange disconnect in (of all places) Yorkville between Yonge St and the centre of what we now think of as Yorkville, the area west of Bay St.

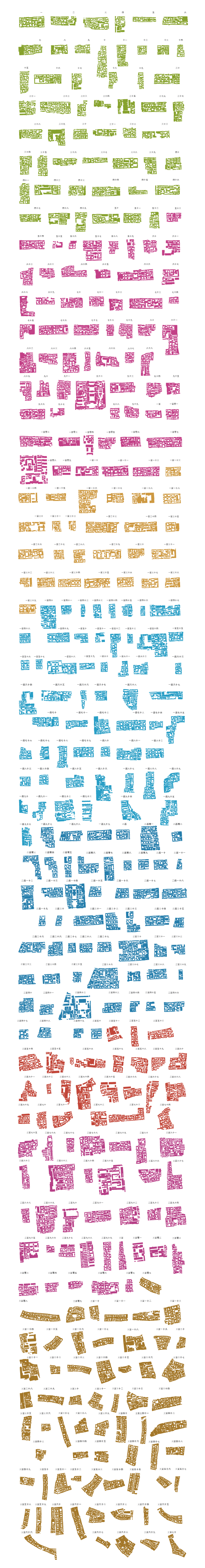

The jog on Bay St creates one of Toronto’s most spectacular urban design moments, but it was far from deliberately planned that way – the placement of the tower of Old City Hall simply took advantage of a precondition in which Bay St ended at Queen St. What is today Bay St north of Queen St was originally a separate street running between Queen St and College St called Terauley St. Terauley St and the grid north of Queen St were originally laid out as part of a separate estate that did not line up with the grid south of Queen (even University Ave did not originally extend south of Queen St, whereas Yonge St was the exception as it was the original concession road).

North of College St there was a one block break, and then a series of streets with slightly different alignments (called St Vincent St, Chapel St and North St) continued the rough line of Terauley St north to Bloor St. North of Bloor St, no streets crossed through Yorkville along the Terauley St alignment. In the early 1920’s, the City decided to cut the Terauley alignment all the way through from Queen St to Davenport Rd and rename it as an extension of Bay St. The late date of Bay St’s creation north of Queen partly explains the lack of significant historical buildings along the street.

The effect in Yorkville has been more profound, as Bay St essentially split the old village in two. Originally, the centre of Yorkville was clearly along Yonge St (very few commercial buildings even existed at the time along Bloor St). Both the library and the fire hall were located close to Yonge St on Yorkville Ave. Since the 1920’s and the cutting through of Bay St, the fortunes of Yorkville west and east of Bay seem to have gone in different directions. While Yonge St has lost most of its connection to Yorkville and sense of it’s former individuality, Yorkville west of Bay was destined to become a centre for artists and alternative culture and finally a very unique boutique shopping district, maintaining a significant amount of its character and village feeling.